"If you don't know where you are going, any road will take you there." – The Cheshire Cat, Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

If you've ever sat down to write an information security policy, this sentiment likely rings true deep within your soul. One minute, you sit down to write a policy about implementing strong authentication. Three weeks later, you emerge with a 300-page dissertation weighing the pros and cons of various forms of multifactor authentication for each of the organization's high-risk systems and users.

You sit back to look at your work and think, "Is this a policy?"

There are a lot of ways to write a policy and there are equally as many things to avoid. One way to ensure your policies are successful is to have a well-defined roadmap. At Tandem, when we sit down to write a policy, we break our policies into the following key sections.

Section 1: Policy Statement

The first section of a policy is the policy statement. This statement is the policy itself. Everything else is supporting material. A policy statement is a short summary of what the policy is designed to do and is typically no more than a sentence or two.

For example, an "IT Asset Management" policy statement could say:

"Maintain an accurate asset inventory to identify and classify assets, determine security requirements, manage vulnerabilities, monitor for end-of-life support, and comply with applicable laws and regulations."

This simple statement defines expected behavior and required actions. This is a policy, but it is only the beginning.

Section 2: Commentary

The commentary section is about answering the question, "Why?" Why is the policy important and what do the policy's key terms mean? This section is especially important if the policy is being read by individuals who do not have a lot of outside knowledge on the topic in the context of your business (e.g., the Board of Directors, auditors, personnel, etc.).

Continuing with the example of an "IT Asset Management" policy, the commentary could answer questions, such as:

- Why is an IT asset inventory beneficial for the organization?

- How does it help the organization comply with laws and regulations, like GLBA?

- What do terms like "end-of-life" and "shadow IT" mean?

The answers to these questions are not "policy," per say. However, the answers are very foundational to helping the reader understand the language and intent of the policy.

Section 3: Implementation

The implementation section is about answering the question, "How?" How do you plan to achieve the policy's expectations? This section may also be referred to as "standards" or "procedures." This is the part where the policy ideals become reality.

For example, if the "IT Asset Management" policy statement says to "maintain an accurate asset inventory," then the implementation section would define things, such as:

- How the organization maintains the inventory (e.g., in Tandem, with a spreadsheet, in another program, etc.).

- What types of IT assets belong in the inventory (e.g., hardware, software, personally-owned devices, third-party managed devices, etc.).

- What the inventory would track for each asset (e.g., status, owner, serial number, classification, location, etc.).

- How often the inventory would be reviewed and updated (e.g., daily, weekly, monthly, etc.).

The implementation section takes the policy expectations and breathes life into them. It isn't just about defining behavior. It's about doing what has been defined.

Section 4: Responsibility

The responsibility section is about answering the question, "Who?" Who is responsible for implementing this policy? A policy is only as good as the individuals carrying it out.

For an "IT Asset Management" policy, the person responsible may be someone like the Information Security Officer (ISO) or a Network Administrator, or maybe even both. Shared responsibilities are common in the world of information security and technology, which is why it is so important to have an effective governance structure clearly defined up front. Somebody needs to make the policy happen.

Section 5: Related Policies

Connecting any related policies is not a requirement, but it can improve the quality of life for both the author and the reader.

Some examples of other information security policies which could be connected to an "IT Asset Management" policy could include:

- The "Data Retention and Destruction" policy to ensure any assets which have reached end-of-life are managed appropriately.

- The "Mobile Devices" and "Remote Work" policies to ensure these types of devices are included in the inventory.

- The "Vulnerability and Patch Management" policy to ensure there is a plan for managing and securing all devices on the inventory.

Listing related policies means the same content does not need to be written twice. This is a major time-saver. It can also result in more consistency and accuracy among the policies. To learn why, check out point #3 on our list of common policy writing mistakes.

Section 6: Committee/Team Review Items

"Trust, but verify" has been a long-time mantra of the security community and essentially, this is exactly why this section exists. It isn't enough to write out what needs to be done and assign responsibility to do it. Someone else should check on things and make sure the policy is being implemented according to expectations and if not, do some root cause analysis to figure out why.

For example, on a regular basis (e.g., monthly, quarterly, semiannually, etc.), the organization's security committee can:

- Check the asset inventory to verify it is current.

- Approve new assets for use by the organization.

- Determine if action is required as a result of any recent end-of-life announcements.

Learn more about this topic in our article: How to Conduct a Policy Review Meeting.

Section 7: Threats

Part of the reason information security policies exist is to mitigate the risk of information security threats to the organization. By associating policies with threats from the GLBA risk assessment, it is easy to demonstrate how policies are effectively reducing the risk of those threats.

For example, knowing what IT assets you have and implementing processes to protect them significantly reduces the potential impact of threats like a fire or if the asset is lost or stolen. It can also reduce the likelihood of a threat which emerges due to the use of shadow IT (i.e., assets operating in the organization's environment without the organization's control).

Section 8: Guidance & Frameworks

Map your policies to regulatory guidance and/or frameworks which may apply. It is important to reference the guidance or frameworks which helped define or provided direction for your policy as this lets outside readers know the policy is driven by industry-accepted guidelines or requirements.

For example, an "IT Asset Inventory" policy might be connected to:

- FFIEC IT Examination Handbooks

- Architecture, Infrastructure, and Operations Booklet

- Business Continuity Management Booklet

- Information Security Booklet

- NIST SP 800-53 Rev. 5

- MP (Media Protection)

- SR (Supply Chain Risk Management)

- PCI-DSS vs. 4.0

- 9: Restrict Physical Access to Cardholder Data

- 12: Support Information Security with Organizational Policies and Programs

- CIS Controls (v8)

- 1: Inventory and Control of Enterprise Assets

- 2: Inventory and Control of Software Assets

Policies are Living Documents

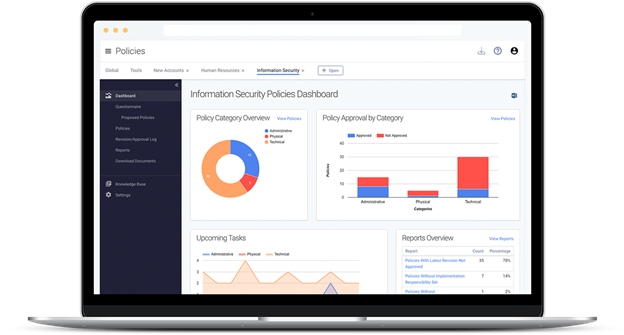

Policies are written at a point in time, but can serve as long-term decision-making tools for your organization. Using a well-defined framework can not only help prevent unnecessary wandering, but it can also make sure you reach your desired destination in a timely fashion. If you would like to learn more about this process, check out Tandem Policies. Learn more at Tandem.App/Policies-Management-Software or sign-up to watch a demo today.